Modules over Principal Ideal Domains (pdf)

We present the fundamental structure theorems for modules over principal ideal domains and provide a selection of their applications. In particular, we show how the Smith Normal Form and the Jordan Normal Form can be derived from these structure theorems.

1. Introduction

Modules over rings are often introduced as a generalization of vector spaces and it is therefore tempting to think of modules in the same way as vector spaces. However, the following pathological example will illustrate that the intuition that we have built up during studying vector spaces is in general not applicable to modules.

Consider the ring and the ideal . Then defines a -module and as such is finitely generated by the set . But

shows that these elements are not linearly independent. In fact, by an analogous choice of coefficients any two elements of are linearly dependent. On the other hand, one can show that is not principal, i.e. there is no single element that generates (one way to do this is by considering the field norm ). This example illustrates a key difference between modules and vector spaces. Namely, if a vector space contains a finite spanning set, then it contains a finite basis. This example shows that this is in general not true for modules. Furthermore, we notice that even though (viewed as an -module) is free of rank one, the submodule is not free and is something in-between the zero-module and . Again this cannot happen in a vector space. If we consider a vector space of dimension one, then the only subspaces are the zero space and the whole space itself.

Remarkably, if we restrict our attention to modules over principal ideal domains, their structure becomes significantly more regular. The rest of this text will be concerned with exploring this well-behaved structure of modules over principal ideal domains and discuss some of its consequences.

In what follows, we assume that the reader is familiar with Ring Theory and the very basics of module theory. However, we do not assume any prior knowledge about modules over principal ideal domains.

2. Structure Theorems

Our first important theorem asserts that if we consider a submodule of a freely generated module over a principal ideal domain, then we cannot end up as in the example provided in the introduction, i.e. the submodule will always be freely generated as well.

We fix a principal ideal domain for the remainder of this section.

Theorem 1

Let be a free module of finite rank over and a submodule. Then is free of rank less than or equal to the rank of .

Proof:

Let be a basis of over . Set

for , where the empty sum is defined as the zero module. We now prove by induction on , that each is finitely generated with rank . The zero-module is free of rank zero, hence the statement holds for . Now assume that the statement holds for . Let be the projection to the ‘th coordinate, i.e. the linear continuation of

for . Then defines a module homomorphism and hence is a submodule of , i.e. an ideal. We now use the fact that is a principal ideal domain to obtain a generator of . If , then by construction and we are done with the induction step. Otherwise, choose . We claim that , which would imply that is free of rank . Indeed, let . Then , hence there exists a such that . This shows that . Furthermore, if , then for some . But since , we have , hence , which implies . This shows that the sum is direct and thus concludes the proof.

Remark 2

Using the axiom of choice one can prove this theorem without the assumption that has finite rank, see (Rotman, 2015).

Next, we will proof another key theorem in the theory of modules over principal ideal domains. It is essentially a statement about finding aligned bases of a module and a submodule, as we will illustrate after we give the proof.

Theorem 3

Let be a free module over , and let be a finitely generated submodule. Then there exists a basis of , elements , and non-zero elements such that

and .

Proof:

We first notice that given a basis of , we can write each generator of as linear combinations of finitely many elements of said basis. Since is finitely generated, we obtain a finite set of linearly independent elements of that generate a free submodule such that . We can thus assume without loss of generality that has finite rank.

We note that in the case where or is the zero-module the theorem holds trivially. We may thus assume for a smoother argument that neither nor is the zero-module.

To begin, let us consider the set of ideals

Since is a principal ideal domain, the above set contains a maximal element under inclusion, say for (see Lemma A2 for details). Again using the fact that is a principal ideal domain we find an such that . Let be such that . We claim that for any we have . Indeed, let be a greatest common divisor of and and let be such that (this is possible since is a principal ideal domain). By construction we have and now maximality of implies . This shows that is a divisor of and hence , as claimed. Finally, we note that the assumption that is not the zero-module implies that .

Let be a basis of and write with for all . By considering the functionals given by the projections onto the ‘th coordinate with respect to the basis , we obtain with the conclusion of the previous paragraph that for all . Thus, there exists an element such that . Finally, we notice that linearity of together with imply that .

We now claim that may be decomposed in to the direct sum

Indeed, let , then

and hence . This shows . Now, let . Write for some . Then, we obtain . Since , this yields and so . This shows and thus the above decomposition into a direct sum holds. Using the fact that , an analogous argument shows

Now if is the zero-module we are done. Otherwise, we apply Theorem 1 to obtain that is again a free module of finite rank and a finitely generated submodule. We can thus inductively repeat the whole argument to obtain the decompositions

where is a possibly trivial free submodule of . Finally, we claim that this construction yields , without any further modifications. Indeed, let denote the projection of onto the coordinate of and consider the functional . Then and hence . But by maximality of we have . We now obtain , i.e. . Once again, by repeating this argument inductively we obtain , thus concluding the proof.

Remark 4

We note that in Theorem 3 we can always append zeros to the sequence of ‘s such that in the case where as finite rank, we have

with .

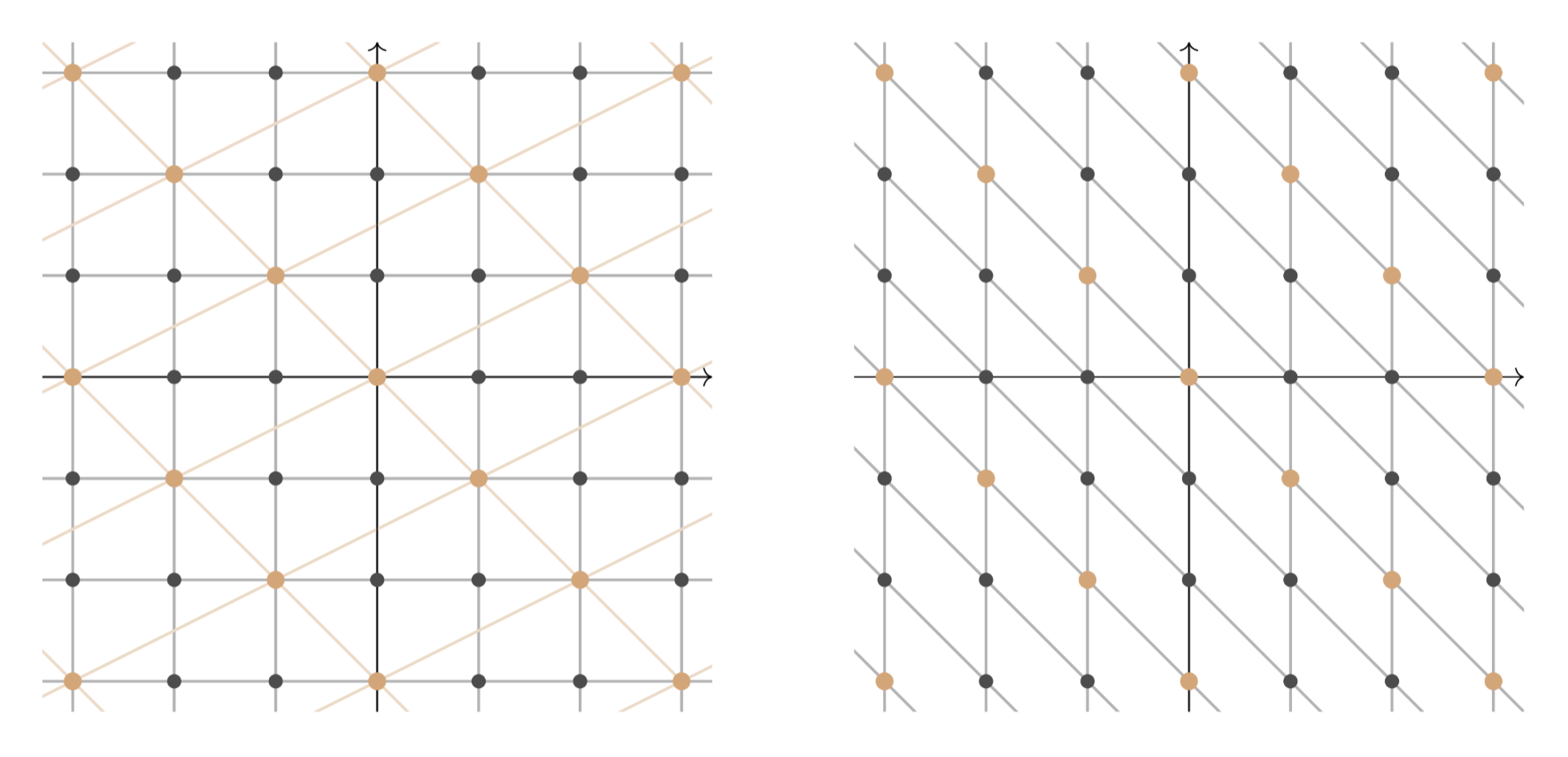

As promised, we will now provide an illustration of Theorem 3. Consider the Gaussian integers viewed as a -module and the submodule generated by and . If we consider the decompositions and , then these are not aligned, as the left hand side of following figure shows. However, Theorem 3 asserts the existence of aligned bases. Indeed, we find and . These are visualized on the right hand side of following figure.

The following theorem builds on the previous results to give a complete classification of finitely generated modules over principal ideal domains, showing that every such module decomposes into a direct sum of a free part and cyclic torsion modules.

Theorem 5

Let be a finitely generated -module. Then there exist integers and element such that

and .

Proof:

Let be generators of . Consider the module and denote by the standard basis of , i.e. is the vector with all zeros except a one at the -th entry. Now, let be the linear map that sends to for all . This map is unique and well-defined, because defines a basis of . Since generate , is surjective. Thus, by the first isomorphism theorem we have

Since is free, we may apply Theorem~\ref{thm:elementary_divisors} to obtain a basis of and elements such that and . We claim that

Indeed, consider the map

We notice that defines a surjective module homomorphism. Furthermore, we note that to conclude our claim with the first isomorphism theorem we only need to show that . Let and write for some . Then, if and only if for all , which in turn is the case if and only if . This shows .

Thus, by putting everything together, we obtain

where . There are now three cases of ‘s to distinguish. If is a unit, then is the zero-module, so it does not affect the direct sum and we may thus omit it in the sequence of ‘s. If is zero, then . Let be the number of zeros appearing in the sequence of ‘s. The final case to consider is if is a non-zero non-unit element. We collect these remaining ‘s into a sequence while preserving their ordering, i.e. we still have . Putting things together we obtain

thus concluding the proof.

Remark 6

Next, we show an alternative formulation of Theorem 5 as it is sometimes more useful.

Theorem 7

Let be a finitely generated -module. Then there exist integers , prime elements , and integers such that

Proof:

By Theorem 5 we have integers and elements such that

Since is a principal ideal domain, there exists for each a unique factorization

where is prime and is an integer for each . Collecting all ‘s and ‘s into one sequence each, we obtain from the Chinese Remainder Theorem that

thus concluding the proof.

We conclude this section by proving that the decompositions in Theorem 5 and Theorem 7 are unique in a certain sense.

Theorem 8

The decomposition in Theorem 7 is unique up to reordering of the pairs and multiplication of the ‘s by a unit.

Proof:

Let be a finitely generated -module. Then by Theorem 7, there exist integers , prime elements , and integers such that

Let be a prime element and an integer. We notice that defines a module over . (The action of on is defined by taking any representative and using the action of on . This is well-defined because for any .) Hence defines a vector space over the field . We claim that

Assuming this claim, the theorem follows. Indeed, assume there is another decomposition of the type as in Theorem 7. We know that for vector spaces the dimension is well-defined. So by varying and we see that the decompositions must be the same up to reordering the pairs and multiplying the ‘s by a unit.

It thus only remains to prove the claim. To determine the dimension we note that for vector spaces we know that the dimension is preserved via isomorphisms. So it is enough to consider what happens to the right hand side of the isomorphism in . Consider the composition

Its kernel is exactly , hence as vector spaces. This shows that the contribution of the free part in the decomposition to the dimension of the vector space is exactly .

Let now be a pair occurring on the right hand side of such that . Then we have . So by the third isomorphism theorem we obtain

Hence, the summand contributes exactly one dimension.

Now consider a pair such that . Consider the surjective homomorphism

Then, by unique factorization in we have

Hence, and so the quotient is the zero-module. This shows that in this case the summand does not contribute to the dimension.

Putting the everything together proves the claim and thus the theorem.

Corollary 9

The decomposition in Theorem 5 is unique up to multiplication of the ‘s by a unit.

3. Applications

There are many applications of the theorems proven in Section 2. For this exposition we will focus on matrix normal forms. We begin with the so called Smith Normal Form, which in a way can be viewed as equivalent to Theorem 3, as each follows relatively quickly from the other.

Theorem 10 (Smith Normal Form)

Let be a matrix. Then there exist invertible matrices and , an integer and elements with such that

where the blank entries are zero.

Proof:

Let be the image of in . Then is a submodule and by Theorem 3 there exists a basis of and non-zero elements such that . Let be such that for each . By construction, linear independence of the ‘s implies linear independence of the ‘s. By Theorem 1, is a free submodule. We claim that any basis of expands the ‘s to a basis of . Indeed, let and write for . Then by construction we have . In addition, we also have . This proves that , hence our claim. In particular, there exists such that defines a basis of . We now obtain the following commuting diagram.

We see that by viewing and in the bases given by the ‘s and ‘s respectively the linear map induced by simplifies significantly. Let denotes the change-of-basis matrix that goes from the basis to the standard basis , i.e. for all . Furthermore, let denote the change-of-basis matrix that goes from the standard basis of to the basis , i.e. for all . Together with the commutative diagram we see that this choice of and conclude the proof.

Next, we explore how the Jordan Normal Form arises as a consequence of the structure theorems presented in Section 2. Recall that the Jordan Normal Form is a statement about endomorphisms of vector spaces. At first glance, it may not be apparent how the theory of modules over principal ideal domains is useful in the more structured and well-behaved realm of vector spaces. The following construction will clarify this connection.

Let be a vector space over a field and an endomorphism of . Then by defining

we can view the pair as a -module. Conversely, let be a -module. Then, by restricting the multiplicative action of on to , we see that defines a vector space over . Furthermore, if we define via , then we have and the action of on is consistent with the one defined above. This construction shows that the study of pairs corresponds to the study of -modules.

Before we begin, a note on notation. Given a vector space over a field and an endomorphism , we will write to emphasize the -module structure induced by the construction above.

Lemma 11

Let be a field and let and be vector spaces over . Let further and be endomorphisms of and respectively. Then and are isomorphic as -modules if and only if there exists a vector space isomorphism such that .

Proof:

We first assume that there exists a -module isomorphism . Then can be viewed as an isomorphism between and with the additional property that for all . This implies for all . Hence, .

Let us now assume that we have a vector space isomorphism such that . Then, we have , i.e. for all . By induction on the degree of the polynomials, we obtain that is -linear. Hence defines a module isomorphism between and .

Lemma 12

Let be a field and for some and some integer . Consider the -module and let be the corresponding endomorphism (according to the construction above) defined by . Then there exists a -basis of such that

Proof:

We claim that the ordered set defines a basis of . Indeed, we first notice that by the euclidean algorithm any equivalence class in has a representative with degree . Thus, for an arbitrary we may assume that has degree . It is then clear that lies in the linear span of . But by considering the linear combination and substituting every with an , we see that spans . We also find that if for some ‘s in , then by comparing coefficients starting with we find that for all . This shows that defines a -basis of . We now notice that

for all and

This shows that is of the desired form, concluding the proof.

Theorem 13 (Jordan Normal Form)

Let be an algebraically closed field, a finite dimensional vector space over and and endomorphism of . Then there exists a basis of such that is in Jordan Canonical Form, i.e.

Proof:

We view as a -module as defined in the construction above. We note that since has finite dimension over it is certainly finitely generated as a -module. Furthermore, we know that is a principal ideal domain. Thus, we may apply Theorem 7 to obtain

for some integers and prime elements . We will denote the right hand side by . Let be a -module isomorphism. As discussed before, we may view as a vector space isomorphism and therefore has finite dimension over . This forces .

By our assumption that is algebraically closed, we obtain that the prime elements of are exactly given by all linear polynomials. Using this and the fact that associate elements generate the same ideal, we may assume that for some for every . We may now apply Lemma 12 to each summand of to obtain a -basis of such that

where is the vector space endomorphism of defined by . Let be the dimension of (and ) over and denote by the vector space coordinate map corresponding to the basis of . Then by Lemma 11 the following diagram commutes.

Hence, if we let be the basis of corresponding to the standard basis of via the vector space isomorphism , then we have , thus concluding the proof.

Remark 14

The assumption of an algebraically closed field in Theorem 13 may be relaxed to requiring that the characteristic polynomial of splits over . This stronger version, can also be proven using the same strategy. However, it would require some more work relating the characteristic polynomial of to the irreducible polynomials obtained from the decomposition of Theorem 7.

Remark 15

Following the same strategy of Lemma 12 and Theorem 13 but choosing the basis for , where denotes the degree of , gives rise to the so called Frobenius Normal Form.

Appendix: Auxiliary Results

Lemma A1

Let be a principal ideal domain. Then satisfies the ascending chain condition of ideals. That is, for every ascending chain of ideals in there exists an index such that for all .

Proof:

Set . One checks that defines an ideal in . Since is a principal ideal domain, there exists an such that . By definition of this implies that there exists an integer such that . Now for any we have have the following chain of inclusions , and hence .

Lemma A2

Let be a principal ideal domain. Then every non-empty set of ideals of contains a maximal element under inclusion.

Proof:

Let be a non-empty set of ideals of . Assume, by way of contradiction, that does not contain a maximal element under inclusion. Let and inductively choose an ideal such that for all . This is possible because otherwise some would be a maximal element under inclusion in . The sequence of ideals defined this way gives a contradiction to Lemma A1, concluding the proof.

References

Hungerford, T. W. (1974). Algebra (Vol. 73). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-6101-8

Lang, S. (2002). Algebra (Vol. 211). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0041-0

Conrad, K. (n.d.). Modules over a PID. Retrieved January 12, 2025, from https://kconrad.math.uconn.edu/blurbs/linmultialg/modulesoverPID.pdf